Gefjun will be forever be famous as the goddess who gave Zealand to Denmark. The Danes immortalized her feat with a fountain in Copenhagen harbour, showing her and her oxen ploughing out the land.

She has many similiarities to Odin, as a goddess who travels between worlds, tricks mortals, and straddles moral and sexual boundaries. Far from being an earth and ploughing goddess, Gefjun is a magical and complex figure.

The main myth about Gefjun, related in two different sources, tells how she got the island of Zealand for Denmark. (It is shown on the map below with the Danish spelling, Sjaelland.)

Snorri tells this story twice, in slightly different ways, in the Prose Edda and Heimskringla. The first book of the Prose Edda is called Gylfaginning, or the “Tricking of Gylfi”. I suspect that the story of Gylfi and Gefjun struck him as a good prelude to his story of how Odin and his two brothers fooled the Swedish king as well:

King Gylfi was a ruler in what is now called Sweden. Of him it is said that he gave a certain vagrant woman, as a reward for his entertainment, one plough-land in his kingdom, as much as four oxen could plough up in a day and a night. Now this woman was one of the race of the Aesir. Her name was Gefiun. She took four oxen from the north, from Giantland, the sons of her and certain giant, and put them before the plough. But the plough cut so hard and deep that it uprooted the land, and the oxen drew the land out to the sea to the west and halted in a certain sound. There Gefiun put the land and gave it a name and called it Zealand.

(Gylfaginning 1, Faulkes’ trans.)

In that version Snorri keeps Odin’s tricks separate from Gefjun’s, but in the Heimskringla, he makes her trick Odin’s idea. In this version Odin sends her to Gylfi, and later marries her to his son:

Thereupon he sent Gefjon north over the sound to seek for land. She came to King Gylfi, and he gave her a ploughland. Then she went to Giant-land and there bore four sons to some giant. She transformed them into oxen and attached them to the plough and drew the land westward into the sea, opposite Óthin’s Island, and is [now] called Selund [Seeland], and there she dwelled afterwards. Skjold, a son of Óthin, married her. They lived at Hleithrar. A lake was left [where the land was taken] which is called Logrin. the bays in that lake correspond to the nesses of Selund. Thus says Bragi the Old:

Gefjon, glad in mind, from

Gylfi drew the good land,

Denmark’s increase, from the

oxen so the sweat ran.

Did four beasts of burden–

with brow-moons eight in their foreheads —

walk before the wide isle

won by her from Sweden.(Heimskringla, Ynglinga saga 5)

It’s interesting, by the way, that the two versions of this story vary on whether she already had the sons or produced them for the purpose.

Her time with Gylfi may account for Loki’s accusation in Lokasenna, when he accuses her of prostituting herself:

Gefjon said:

‘Why must the two of you Aesir in here

wrangle with wounding words?

Is it not known of Lopt that he likes to give lip

and that all the gods properly appreciate him?’Loki said:

‘Shut your mouth, Gefjon, now I’ll mention

someone who seduced you to sex:

that white boy who gave you a brooch

and you thrust your thighs over him.’Odin said:

‘You’re quite made, Loki, and out of your mind

to make an enemy of Gefjon:

I reckon she knows all the fates of the world

just as clearly as me.’(Lokasenna 19-21, Orchard’s trans.)

Both Odin’s statement that Gefjun knows fate, and the identity of the “white youth” have spawned much commentary. The most obvious candidate is Gylfi, although another theory says that Gefjun and Freyja are the same goddess, and Freyja was perhaps thanking Heimdall for getting her necklace back.

Whether Freyja and Gefjun are the same goddess or not, one of Freyja’s by-names is Gefn, and some have seen Gefjun as another “giving” goddess. Odin’s statement about fate, however, links her to Frigg, who also can see the future.

Stepping Outside the Bounds

What interests me about the story of Gefjun and Gylfi is that Snorri doesn’t express any disapproval of her. He was a Christian, and while he respected the pagan gods, he could also be very censorious about their behaviour. I suspect that Gefjun was popular with the Danes, to get off so lightly.

The other thing that strikes me is how Odinic her story is. She fools Gylfi, like Odin does, using her four sons by a giant to take a large portion of Gylfi’s kingdom for the Danes. You could see it as a variant on the story of Odin and the mead of poetry, where he fools the giant who holds the mead, sleeps with his daughter to get access to it, then flies off with it to share with humans.

Also like Odin, she travels to Gylfi’s court, and then to Jotunheim, which we are told is far away and hard to get to. Usually it’s Odin or Loki who do the travelling, with Thor occasionally faring eastward to smash giants. Goddesses don’t get around much.

Also, we have to assume that she was persuasive enough to get Gylfi to promise her the land in the first place. She came to him as a “vagrant woman”, just as Odin often disguised himself as a wandering old man.

The poem Snorri quotes to back up his story, Ragnarsdrapa, makes Gefjun’s plowing sound rather violent, with its steaming oxen and the plough ripping into the earth (giant excess again?). Karin Olsen suggests that the skald intended to remind us of Odin and his brothers ripping Ymir apart to make the world. Like them, she is both creator and destroyer. (Olsen: 125)

Odin was not shamed by his frequent liaisons with giantesses, and Gefjun was still of good enough standing to marry one of Odin’s sons, and become the ancestress of the Danish royal family. Still, you have to wonder.

If Freyja refused marriage to a giant because she feared that even she couldn’t satisfy a giant’s appetite, what does that say about Gefjun? It might explain how she had four sons from that liaison, though. (And might tie in with Loki’s accusation that she “thrust her thighs” over someone, suggesting that she was the dominant sexual partner.)

Disqualified as a goddess?

That Snorri continued to count her among the goddesses, listing her third or fourth after the Big Two, Frigga and Freyja, flies in the face of a currently popular theory about Norse myth. This suggests that while it’s okay for the gods to sleep with or have a regular liaison with giantesses, the other way around is taboo. Scholars base this on two things:

- the gods do frequently pair up with giantesses, but marry only their own kind.

- the giants keep trying to get Freyja, Sif, or Idunn for themselves, but are killed by the gods.

A refinement of this is the idea that Loki’s mother Laufey is a goddess who “transgressed” in having children for a giant. John Lindow, in his guide Norse Mythology, seems rather baffled by Gefjun, and argues that she isn’t really a goddess, because she has also has children with a giant, and suffers no penalty.1

Lindow was one of the scholars who developed this theory of Loki and his mother, and it makes a lot of sense when you think about how Loki is viewed in Norse myth. But that ambivalence shading into hostility doesn’t apply to Gefjun.

However, Else Mundal points out she and Idunn are almost never used by the skalds in their kennings for women, unlike Freyja and Hlin. So there may be something to the idea of a “giant taint”. (The exception is in Haustlong, and uses Gefjun’s name to refer to the volva Groa, living among the giants. Was Gefjun seen as similarly outside normal society by some?)

If you were conspiracy-minded, you could also point out that she’s only mentioned once in the Poetic Edda, and that is when Loki insults her. But considering how little we have about Eir, Vor, or Fulla, even an insult would be an improvement.

Icelandic scholars were not so picky, however, as they used Gefjun to gloss the names of many prominent Roman goddesses in translations of Latin texts. Diana was the most common, but Vesta, Minerva and Venus were also compared to Gefjun. (French:19) (Freyja was the more usual gloss for Venus.2)

But doesn’t she protect virgins?

In Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, he mentions her in his list of goddesses, saying:

Fourth is Gefiun. She is a virgin, and attended by all who die virgins. (Gylf 15)

What makes this so odd is that the introduction to Gylfaginning tells the story of Gylfi and Gefjun, setting the stage for Odin fooling him again. Some scholars have suggested that the Gefjun story was added later, but then Snorri tells it again in Heimskringla, quoting a 9th-century source to back it up.

That poem, Ragnarsdrapa, is known only from Snorri’s quotes from it, so presumably he knew it well. Bragi Boddason, the skald who composed it, put it in the form of a description of scenes on a shield, so he clearly expected people to know the story of Gefjun. (If his poem was based on a real-life shield, then so did the artisan who made it.)

Added to that is the rather odd horse-play in the story Volsa thattr, which recounts a pagan custom (which may or may not be real), of passing around a preserved horse’s penis while reciting verses, apparently made up on the spot. The unmarried daughter of the house, when her turn comes, says:

I swear by Gefjun

and the other gods

that against my will

do I touch this red proboscis.

May giantesses

accept this holy object,

but now, slave of my parents,

grab hold of Völsi.

In addition, Gefjun is identified with Diana in Breta sögur and Minerva in Trójumanna saga, both virgin goddesses. (As I pointed out above, though, one writer saw her as Venus, so that’s not an open-and-shut argument.)

Does it matter?

In a certain sense, no.

I mentioned above that her name is often connected with Freyja’s by-name Gefn. This in turn is often associated with the cult of the Matres. These mother-goddesses often have names ending in -gabi, which are normally interpreted as connected to words meaning “giving”. (But see below.)

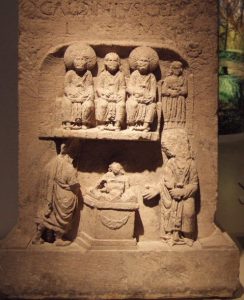

Sometimes images of the Matres show two women with babies or the hairdos of mature women, while the third has her hair unbound, like an unmarried woman would, showing that they governed both phases of a woman’s life.

The Aufanian Matronae (detail) from the Gallo-Roman temple site at Görresburg, Nettersheim. Picture by Leonce49, Wikimedia.

Linguists think that “Gefjun” may be the source for a Finnish word meaning “bride’s outfit, trousseau”. This suggests that rather than being protector of virgins exclusively, Gefjun may have been a protector of young women, especially those of marriagable age. This limnal state, neither girl nor mature woman, could warrant a special goddess, like the Greek Artemis, as a protector and guide. (This idea was inspired by Helio’s comment and a further reading of Lindow’s entry on Gefjun.)

Kevin French proposed in his thesis that Gefjun’s name, far from indicating a fertility-goddess or personfication, should be connected to words like the Old Icelandic gǫfugr ‘noble’ and Gothic gabei ‘riches’. He suggests that Gefjun would mean something like: she who rules/pertains to *gaƀī. (Itself connected to words meaning abundance, nobility and worship.) The -un suffix shows that she is the goddess in charge of those qualities, just as Odin was the god of fury, od.

He suggests that perhaps Gefjun was a leader of the Gabiae, in the same way that “Hludana [was] the leader of the Holden (some sort of spirit, perhaps related to Scandinavian huldrer or the seiðkona Hulð in Ynglinga saga chapter 13)”. Perhaps the various cults of the Matres and Matronae with the “gabi” names such as Garmangabi, Gabiae, Friagabiae and Arvagastiae found a focus in the goddess Gefjun.

This could also explain the maiden’s appeal to Gefjun in Volsa thattr. If Gefjun was a goddess who granted abundance and social position, and was associated with holy rites, then it makes sense to appeal to her during a household ritual which presumably was intended to ensure prosperity and well-being for the people who lived there.

French’s argument may sound a bit odd to a popular audience, but he’s trying to do an end run around a view of goddesses as essentially a symbol of a piece of land, and which sees them as “explained” once they’re tied to the earth. Gefjun is not the living embodiment of an island in Denmark, but a concious being making choices, travelling between worlds, morally and sexually ambivalent, creator and destroyer, and possibly endowed with prophetic insight.

1. Snorri Sturluson places her among the goddesses, listing her third after Frigg and Freyja in Gylfaginning, and fourth in another place, after Frigg, Freyja and Eir.↩

2. The historical collection Stjórn refers to Gefjun as Venus.↩

References:

Edda, Snorri Sturluson/Anthony Faulkes, Everyman Press, Penguin, 1992. (reprint)

The Elder Edda, a Book of Viking Lore, Andy Orchard (trans.), Penguin Classics, 2011.

Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway, Snorri Sturluson/Lee Hollander, University of Texas, 1964/92.

French, Kevin 2014: “We need to talk about Gefjun: Toward a new etymology of an Old Icelandic theonym”, diss. (pdf available here)

Lindow, John 2001: Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs, OUP.

Mundal, Else 1990: “Position of the Individual Gods and Goddesses in Various Types of Sources – With Particular Reference to the Female Divinities”, in Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place Names, ed. Tore Ahlback, Almqvist & Wiksell Internat: 294-315. (pdf here)

Olsen, Karin 2001: “Bragi Boddason’s Ragnarsdrapa: a Monstrous Poem”, in Monsters and the Monstrous in North-West Europe, eds. Karin Olsen and Luuk A. J. R. Houwen, Peeters Publishers: 123-40. (Google Books)

Simek, Rudolf (trans. Angela Hall) 1996: Dictionary of Northern Mythology, D. S. Brewer.

Two authors on Gefjun and other Norse goddesses:

dooley, d. Kate 2006: The Spinde Hearth: A Sourcebook for Goddess-Centered Living, Yarrow Press, Asheville-Lewisburg.

Karlsdottir, Alice 2003: Magic of the Norse Goddesses: Mythology, Ritual, Tranceworking, Runa-Raven Press.

(And my own Asyniur: Women’s Mysteries in the Northern Tradition.)

Links (Some other views of Gefjun):

Norse Mythology for Smart People (takes the “Gefjun as earth” view)

Diana Paxson on Frigga’s Handmaidens

Journeying to the Goddess on Gefn and Gefjun

Odin’s Volk: short bio

Gods Laid Bare (from the Wayback Machine; connects Frigg and Gefjun)

Very well done! There’s a lot of work in this, so congrats. There are two things I’d like to point out.

1) She may be a giantess, but that doesn’t necessarily disqualify Her as a goddess. Skadi, for instance, is both and since we have only fragments of a mythology, it may well be that we just don’t know Gefjun’s myth of integration into the divine community;

2) As for Her identification with Diana, Minerva and Venus, that sort of equation is basically a matter of focusing on similarities and ignoring the differences. A prime example is the Egyptian Bast, who was identified with both Artemis and Aphrodite, the former because Bast has a huntress aspect and latter because She’s also a goddess of lust. So it may be that Gefjun had a similar mix of features, perhaps even being a deity who presided over sexual maturation or transition and thus linked to both love and virginity. This would also match Her somewhat liminal nature.

And again, great post!

LikeLike

Both of those are extremely good points. I have been thinking about a post on the extremely thin boundary between gods and giants, and Gefjun might be a good entry point for that.

I didn’t really consider the identification much, but it is true that since most deities have several different aspects, they can usually be compared to a number of different deities in another pantheon.

I’m glad you liked the post, though. I wasn’t sure I’d get a thousand words on Gefjun, but that post would not stop growing! I keep feeling there’s more I could have said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have no scholarly comment to add. I simply read. This whole world of mythology is fascinating and so much a part of ancient cultures. (do you know if New Zealand has any connection to Gefjun and Zealand?) The Maori of N.Z. have an amazing culture with a very almost viking slant on some mythology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s named after a part of the Netherlands, so no.

LikeLike

Pingback: Gefjun: goddess or giant? – WE ARE STAR STUFF

Pingback: Travelling Vanir: Freyr, Nerthus and Njord – WE ARE STAR STUFF

Pingback: Garmangabi: Matres and Mortality – WE ARE STAR STUFF

Pingback: The Wild Hunt – WE ARE STAR STUFF

Pingback: Idunn and Helen: People or Property? – We Are Star Stuff

Pingback: Why Is Tyr Such an Unimportant God? | We Are Star Stuff

Pingback: Why Is Tyr Such an Unimportant God? | We Are Star Stuff

This was very interesting to read. I am writing a book whose theme revolves around fertility, and the statue of Gefjen in Copenhagen is mentioned, so I was looking for a little more about the fertility aspect of Gefjun. Do you know anything more about how she helped in fertility or reproduction or protecting the womb, etc…? Thanks!

LikeLike

If Gefjun is a goddess who gives fertility, it’s hard to tell from the sources. Her famous plowing is seizing land, not farming it, and of course the Prose Edda says she is protector of unmarried women. Her name suggests a “giving” goddess, and if we see her as a protector of women of marriageable age, then she would be a protector of these women and their potential fertility. So I don’t think Gefjun is a goddess of fertility in any direct sense, although her connection to the mother goddesses might be an argument for her as a goddess whose gifts include fertility.

(The links I gave in the references take different views on this; and obviously Kevin French’s thesis doesn’t accept the Gefjun = fertility equation, although it’s a very thorough look at Gefjun.)

LikeLike

Thanks for that response. I’ve seen her listed as a goddess of fertility on various websites, but maybe because she is also sometimes said to be the same as Freya? Either way, I will take your word for it. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for that. One of Freya’s bynames is Gefn, that’s probably how that got started.

LikeLike

Pingback: Hlin: Protector Goddess | We Are Star Stuff