When the Roman poet Lucan wanted to show the savagery of Gaulish religion, he used the bloodthirsty cults of three Gaulish gods to make his point: Taranis, Toutatis and Esus. While the first two had well-established cults in Gaul and Britain, Esus is more elusive.

Woodcutter God?

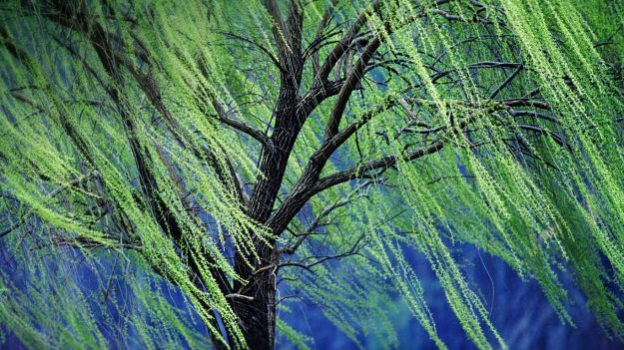

There are two known images of Esus, and they are strikingly similar. The more famous is the Parisian one, one panel on a stone pillar dedicated by the local boatmen, presumably a guild. The panel is inscribed with the name “Esus” and shows him cutting branches from a tree, possibly a willow. Neither of the other gods Lucan mentions appear on the pillar, although Volcanos, Jupiter and the Celtic Tarvos Trigaranos (bull with three cranes) are among the other deities honoured.

The other image of Esus comes from Trier, in Germany . It keeps the woodcutter imagery, and adds a bull’s head and three cranes, presumably a reference to Tarvos Trigaranos. The other side of the stone shows Mercury and a goddess, probably Rosmerta. (They may also appear on the Paris monument: Mercury can be identifed by his attributes, but unfortunately the goddess with him is more generic.)

The caption to the photo below comes from the Rheinisches Museum, translated:

The sacred stone is one of the most important monuments of Gallo-Roman religious history. The obverse shows the Roman god Mercury with a companion, most likely the Gallic mother goddess Rosmerta. The Gallic god Esus is shown on the right side. He seems to have had a protective function. The inscription on the front reads: I] ndus Mediom (atricus) Mercurio v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) merito) Indus, the mediatrist, has gladly fulfilled his vows to Mercury.

Presumably there was some story connected to the image of the god cutting wood, whether he was seeking material for shipbuilding, or something more metaphysical (Miranda Green suggests he’s cutting back the Tree of Life).

Two possible parallels are the story of Indra killing Trisiras and the life of Cúchulainn. The Vedic thunder-god killed Trisiras after he grew too powerful, but he needed a woodcutter to cut off his adversary’s three heads. A bird flew from each neck as the heads were severed.

In the Irish epic the Táin, three birds warned the great bull of Cooley that Cúchulainn is coming for it, and he cut down the trees to block the advance of Queen Medb’s army. (It does seem a bit of a reach, seeing as these are two separate events, and the tree-cutting is hardly a major part of Cúchulainn’s story. Also, the Morrigan appeared in crow form, not as a heron.)

Esus, Hesus, Aisus

You would hope that perhaps Esus’ name might help us with some clue as to his function. Taranis, after all, has to be a thunder-god, while Toutatis is obviously the protector of the tribe. However, the most popular interpretation isn’t much help. Puhvel and Duval suggest “lord” or “master”, citing the Latin erus, master, as a parallel. Like Toutatis, it could be either a name or a title. (The Norse name Freyr has a similar meaning, and ambiguity.)

The other possiblilty isn’t a lot more helpful – Vendryes’s theory that it comes from IE *esu, good. Further, Le Roux and Guyonvarc’h suggest that esus may just be a title of the Dagda‘s (known as the Good God), like optimus for jupiter.

While the Paris inscription calls the god Esus, the Roman poet Lucan refers to him as Hesus in his verse on Gaulish gods:

And those who pacify with blood accursed

Savage Teutates, Hesus’ horrid shrines,

And Taranis’ altars, cruel as were those

Loved by Diana, goddess of the north;

All these now rest in peace.

(Lucan, De Bello Civilo [Pharsalis] I: 498-501)

However, the Gaulish writer Marcellus of Bordeaux may have mentioned Esus in his medical treatise, The Book of Medicaments. Although he wrote in Latin, he included a charm for throat aliments in Gaulish, invoking Aisus. Allowing for oral transmission, the names aren’t that different. The charm goes:

Xi exu crion, exu criglion, Aisus, scri-su mio velor exu gricon, exu grilau.

Rub out of the throat, out of the gullet, Aisus, remove thou thyself the evil out of the throat, out of the gorge.

(Must: 197)

Personal names included Esus, usually invoking his strength or presence: Esumagius (“he who is as powerful as Esus”), Esugenus (“son of Esus”), and Esunertus (“he who has the strength of Esus”). The last one appears on an altar dedicated to Mercury in Germany. The Esuvii of Normandy and the Esubiani (Vesubiani) possibly from the south-west of France, may have been named for him. (Ency. Rel. V: 167) If the Essuvi were his followers, it may be their cult that is recorded on the Paris monument.

Mercury or Mars?

The Berne Scholia, a commentary on Lucan’s epic poem, and two other glosses on Lucan, all represent later interpretations of the gods Esus, Taranis and Toutatis. I quoted the Berne Scholia in my post on Toutatis, but briefly it compares Esus to Mars and Toutatis to Mercury. However, the other commentaries reverse this. The Cologne Manuscript and another set of annotations both agree that Esus is Mercury, while Toutatis is Mars.

It seems intuitively right that the tribal protector Toutatis would be associated with Mars. Whether Esus was really comparable to Mercury is an open question. Both gods are depicted on the Trier altar, perhaps the religious equivalent of a billingual sign? Julius Caesar observed that Mercury was the most important Gaulish god, although that doesn’t fit with Esus’ relative obscurity. (Caesar gave the god a Latin name, of course.)

Jan de Vries and Jaan Puhvel both take the Esus/Mercury comparison further, seeing a strong resemblance between Esus and Odin. The Berne Scholia says that Esus’ victims were hung in trees, much as Odin himself hung in a tree, and hanging is a recurring element in his myths. The Germans certainly saw parallels between Mercury and Odin, both travelling, clever gods.

The Tree of Life?

Looking again at Esus’ imagery, you notice how much is to do with marshlands. The herons or egrets that sit on the bull’s back live where land and water meet, as does the willow tree that Esus is cutting (or pruning – another interpretation!). Willows have been pollarded (cut back hard periodically to harvest the branches) since medieval times, and their regeneration, as well as their ability to root when used as stakes or fencing, has always been impressive. It’s not hard to imagine Esus as a deity of cyclical life, symbolized by water and the deciduous tree that roots itself anywhere it’s stuck. (Miranda Green seems to lean toward this theory.)

However, the one disappointing thing about Esus is that compared to Taranis and Toutatis, he is not a well-attested deity. There are no other altars to him, no rings with his name engraved on them, no other art with his image. Lucan, writing in Rome, may have intended them as a Gaulish version of Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus,1 perhaps with Esus as a similarly obscure third god.

1. Although once again there is disagreement about which god matches which. Jupiter and Taranis are an obvious pair, while Toutatis would seem to equate to Mars, leaving Esus as Quirinus. But Puhvel and some other scholars pair Toutatis and Quirinus, as gods of the populace, making Esus Mars. ↩

References and Links:

n.a. 1897: “Archaeological News,” American Journal of Archaeology 1 (4/5): 374-5. (JSTOR)

Duval, Paul Marie 1989: “Teutates, Esus, Taranis,” in Travaux sur la Gaule (1946-1986): École Française de Rome: 275-287. (Persée)

Green, Miranda 1997: Dictonary of Celtic Myth and Legend, Thames and Hudson.

Must, Gustav 1960: “A Gaulish Incantation in Marcellus of Bordeaux”, Language 36/2/1 (Apr-Jun 1960): 193-7. (JSTOR)

Puhvel, Jaan 1987: Comparative Mythology, The John Hopkins University Press.

Chronarchy.com on Esus (This is almost a one-stop shop on Esus)

Esus – described by the Romans as a Barbarous Celtic God

Mary Jones on Esus

Arbre Celtique (in French)

Au dieu Mercure (in French)

For the image at the top, click here.

Fascinating stuff. I’d definitely agree with a marshland connection with the willow, aurochs, and cranes/herons/egrets. Wasn’t Paris originally very marshy? I’d agree that Esus may have something to do with the cutting and regeneration of the willow, which must have been useful for building and weaving. I wonder whether the sacrifices in trees were to him as a guardian deity of willowy marshland?

I hadn’t come across the Vedic story before but love the way the birds fly out of the enemy’s head. Seems connected with the flight of the soul(s). There’s a lot of depth to this imagery.

LikeLiked by 3 people

There is. I hadn’t thought about the geographic aspect, but it makes sense. It’s a great pity we don’t know more about Esus.

LikeLike

Good article… Thank you. On the geography, there is an area in central Paris (3rd and 4th arrondissements/areas) called Le Marais, which means Marsh… so, interesting…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very. Maybe this marshy area of Paris inspired the myth around Esus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was very interesting (again :)) – and the parallels with Irish, Norse and Vedic traditions very intriguing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Dragon Prow Shadow and commented:

a strong resemblance between Esus and Odin. The Berne Scholia says that Esus’ victims were hung in trees, much as Odin himself hung in a tree, and hanging is a recurring element in his myths. The Germans certainly saw parallels between Mercury and Odin, both travelling, clever gods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Could Esus’ shrines have been sacred trees or groves, similar to those in India? If they were cut down at a later stage there would be no trace of them, except in place-names.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could be. Other deities like Nemetona were likely associated with trees, so it’s possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Lugos and Gaulish Mercury | We Are Star Stuff