Most of us have at least toyed with the idea of a voodoo doll, but we wouldn’t really curse someone… would we? The people of the ancient world weren’t so shy, and have left us a lot of their ill-wishing to study. The things that made them angry enough to curse someone aren’t so different from the things that annoy us now: lawsuits, theft, property damage, infidelity, stealing someone’s boyfriend/girlfriend, and so on.

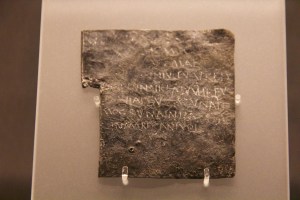

These spells were known as katadesmoi in Greek or defixiones in Latin; the Greek implies binding, while the Latin connotes “nailed down”. The most common format was an inscribed lead tablet which was rolled up and hidden somewhere to do its magical work. (Lead was cheap, easy to write on, and was the colour of the dead, no doubt enhancing its magical power.)

Faraone’s essay in Magika Hiera, a study of ancient Greek magic, lists four types of spells:

- direct binding formulas: “I bind NN”

- prayer formula: “May the gods (named or not) bind NN”

- wish formula: “May NN be unsuccessful!”

- simila similibus formula: “Like this corpse is lifeless, may NN be lifeless”

We have about 1600 such spells from the ancient world. At least six hundred such spells were found in Greece, with many more from Rome and the various outposts of the Empire. (Faraone: 3) Britain in particular seems to have plenty of curse tablets: at least 250 of the Latin tablets come from there.

Pliny observed that “there is no one who does not fear to be cursed by spell tablets.” (Natural History 28.4.19). There are stories of how Thucydides was stopped mid-flow in court by a spell, and Cicero blamed magic when forgot the details of a case, so we know that they were considered a real menace. (And a believable excuse.)

Cursing as a profession

Cursing people was so common it was an industry – part of a professional magician’s trade along with healing spells and love-charms. Some ancient Greek papyri, known as grimoires, give formulae for preparing a spell. There are similar documents in Syrian and Arabic such as the Picatrix. (Gager:72)

We know that professional magicians existed, since various ancient texts refer to them, from plays and novels all the way to philosophy:

…begging priests and soothsayers go to rich men’s doors and make them believe.. that if a man wishes to harm an enemy, at slight cost he will be enabled to injure just and unjust alike, since they are masters of spells and enchantments that constrain the gods to serve their end.

(Plato, Republic 364 c)

The professional touch might explain why so many of these curse tablets read as if copied from each other: a lot of them came from “recipe books” that gave formulae for cursing rivals. Despite this, you do get the occasional do-it-yourselfer whose tablet takes an unusual format, and the formats themselves change over time. Some of the later Roman and Greek ones invoke Jesus and Mary, for example. (Gager: 71)

Fifteen defixiones found in a well seem to have been written by the same person, using the same formula, and another set of eight from a columbarium on the Appian Way have the same formulae and drawings. A scribe presumably did the 20 katadesmoi found in wells around Athens, all in the same writing, with the same text. (Faraone 23, n. 15)

How do you curse someone?

Most curses were inscribed on a lead tablet. After you’d finished writing out your curse, you rolled it up into a scroll, possibly crushing it in your hand, driving a nail through it or folding it up. Then you put it somewhere magically significant.

If you were cursing a chariot team, you might place it in the stadium. Other places included wells (the well in the sanctuary of Anna Perenna in Rome was full of them, as was Sulis Minerva‘s spring in Bath), cemeteries, sanctuaries and temples, and the victim’s home.

Sometimes people added an actual figure – a real “voodoo doll” – to the tablet, rolling the scroll around it. (Many more spells than we know probably used figures, since many of them have probably decayed over time, leaving the lead tablet behind.) You could also add some of the victim’s hair, especially for love-spells.

A little lead “gingerbread man” found at Carystus on the island of Euboea, seems harmless until you read the two inscriptions:

I register Isais, the daughter of A(u)toclea, before Hermes the Restrainer. Restrain her by your side!

I bind Isais before Hermes the Restrainer, the hands, the feet of Isais, the entire body.

(Faraone: 3)

Another found in Rome was a folded tablet inscribed with a smiling figure, its torso bound in cords, the head and shoulders pieced by nails, and surrounded by a snake poised to strike. The curser was taking no chances. (Adams: 3)

To make it more magical, you could add Greek letters, foreign names of deities or spirits (usually Persian, Egyptian or Hebrew – Adonai and IAO were used), reversed or scrambled names, and made-up words known as voces magicae, words imbued with magical power. (The “barbarous names of evocation” worked on this principle.)

While early curses were fairly simple (“I bind NN”) they became more elaborate over time, naming various demons and deities. The chthonic deities like Pluto and Prosperine were favourites, but the British tablets in particular tend to be addressed to “normal” deities like Jupiter, Neptune, Diana, Mercury and Nemesis, as well as Sulis Minerva and Nodens. (The one to Nemesis asks for a theft to be avenged, so it makes sense.)

A couple of spells from Gaul address themselves to the “underworld gods”, the andedion, presumably the local equivalents of Pluto and Prosperine.

Love Magic

Two categories of cursing/binding magic are a bit special, love magic and the prayers against thieves and other criminals. The love magic spells are about binding than cursing, but by today’s standards they fall well short of consent, as they are intended to make someone fall in love or sleep with you whether they want to or not.

Erotic spells often used wax images of the intended victim, and sometimes the client as well. (Gager: 74)* An early Greek love spell reads:

[I bind?] Aristocydes and the women who will be seen about with him. Let him not marry another woman or matron.

There are many more like this, including one that asks that Zoilos be powerless to come to Anatheira, just as the corpse the spell is buried with is powerless. (Faraone: 13)

The love spells show a gender divide, according to scholars: women’s spells tend to use the word philia, and try to increase affection between women and men, while men’s spells tend to use the word eros, and try to force the woman out of her home and into her lover’s arms. (Gager: 79-80) This quote from a much longer spell gives you the idea:

..Drag her by the hair and heart until she no longer stands aloof from me, Sarapammon, to whom Area gave birth, and I hold Ptolemais myself, to whom Aias gave birth, the daughter of Origenes, obedient for all the time of my life, filled with love for me, desiring me, speaking to me all the things she has on her mind.

Complaint about theft of Vilbia – probably a woman. This curse includes a list of names of possible culprits. Perhaps Vilbia was a slave. (Wkimdedia)

Pleas for Justice

The other special category of cursing tablets should be looked at less as cursing and more as “prayers for justice”, according to H.S. Versnel. He argued that given the rudimentary state of law enforcement in ancient times, asking the gods to right a wrong made a good deal of sense.

A few British and Spanish ones were even intended for display: they had little holes drilled in the top so they could be attached to a wall. One Spanish tablet, from Emerita, was of marble rather than lead, making it an offering as much as a curse. (Tomlin: 249) It reads:

Goddess Ataecina of Turibriga, and Prosperina, I ask you by all your majesty, I beg you to avenge the theft that has been done to me, whoever has changed, stolen or diminished the things which are written below. 6 tunics, 2 linen cloaks, a shift (?) I do not know..

The tablet breaks off there, but we get the gist. Another, this time in folded lead tablet form, comes from Uley in Britain, and is more formal in style, like a petition to a local official:

A memorandum to the god Mercury from Saturnina, a woman, concerning the linen cloth which she has lost. (She asks) that he who has stolen it should not have rest before, unless, when he brings the aforesaid property to the aforesaid temple, whether woman or man, slave or free.

The ones with the holes may have been meant to shame the criminal into returning the goods, but others were hidden where only the deity would know about them, like the curse tablets deposited in Sulis Minerva’s spring. They had to substitute for the satisfaction of getting your goods back, and seeing the thief punished.

Adams, Geoff W. 2006: “The social and cultural implications of curse tablets [defixiones] in Britain and on the Continent,” in Studia Humaniora Tartuensia 7:1-15. (pdf here)

Faraone, Christopher A., and Obbink, Dirk (eds.) 1997: Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion, OUP. (Questia)

Faraone, Christopher A. “The Agonisitic Context of Early Greek Binding Spells”: 16-32.

Versnel, H.S. “Beyond Cursing: the Appeal to Justice in Judicial Prayers”: 60-106.

Gager, John G. 2006: “Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in the Ancient Roman World,” in The Meanings of Magic: From the Bible to Buffalo Bill, ed. Amy Wygant, Berghant Books: 69-87. (Google Books)

Jordan, David R. 2003: “”Remedium Amoris”, a Curse from Cumae,” in Mnemosyne 4th series, 56/6: 669-76. (pdf here)

Tomlin, Roger “Catching a Thief in Britain and Iberia,” in Religions in the Graeco-Roman World: Magical Practices in the Latin West, (vol. 168) eds. Richard L. Gordon and Francisco Marco Simon, Brill: 245-74. (pdf here)

Links:

Graeco-Roman Curses

Curse Tablets of Roman Britain

Bath Tablets

For the image at the top, click here.

Wow, those love spells definitely have some uncomfortable wordings.

I find it interesting that the general cursing incantations emphasize binding. Perhaps I’m understanding it differently than its original intention, but wouldn’t “binding” someone you dislike imply that they simply don’t appear in your life? If so, at least that’s better than calling down death on them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Greek translates as “binding”, the Latin as “nailed down”. Suggests to me that unlike what modern Wiccans or other magic users would call a binding spell, these were intended to bind the user to the spell-caster’s will.

LikeLike

Wow! Funny to think that the art of cursing someone is still so prevalent in cultures even today. I wonder if those thieves were shamed into returning those items.

Were there counter-curse tablets or amulets, too?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe so – I should check on that. The curses that were hung up rather than buried suggest that shaming someone into returning your stuff was possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting. Thanks 🙂

LikeLike