Gaulish Alesia, the home of Ucuetis and Bergusia, was nearly lost to history entirely. After Julius Caesar’s military successes in Gaul, the Celtic tribes formed an alliance to push the Romans back, led by the Arverni chieftain Vercingetorix. At first the Gauls scored several victories against the Romans, but at Alesia the Roman army settled down to a seige which only ended when Vercingetorix surrendered.

After that Alesia became a Roman oppidum, and seems to have prospered, becoming famous for its metalworking. In the 5th century, after the Western Empire collapsed, the Gauls abandoned the town. Alesia’s location became a mystery, solved only in 1838 when an inscription, IN ALISIIA, was uncovered. Napoleon III ordered archaeologists to excavate around Mt. Auxois, confirming that Alise-sur-Reine, near Dijon, was Alesia.

The town had lain undisturbed so long, it was an archaeologist’s dream. There was abundant evidence of the two main industries of the town, a healing shrine and numerous metalworkers’ shops. The healing shrine was dedicated to Apollo Moritasgus, while the metalworkers acknowledged the smith-god Ucuetis and the goddess Bergusia.

Ucuetis

One building seems to have been the banqueting and guild hall for the local smiths and metalworkers, with a shrine to Ucuetius in the cellar (see picture below). A bronze vase found there was inscribed with both their names, and other bits of metal found in the cellar, such as door hinges, may have been offerings to Ucuetis.

Another find commemorates the building of the celicnon, or banqueting-hall, and mentions Ucucetis by name. The stone tablet that records the gift, carefully carved and decorated with vine leaves and stylized letters, reads:

Martialis Dannotali / ieuru VCVETE SOSIN / CELICNON ETIC / GOBEDBI DVGIIONTIIO / VCVETIN(?) / in Alisia

Martialis, son of Dannotalus, dedicated to Ucuetis this edifice and for [or with] the smiths who worship Ucuetis in Alesia.

(C.I.L. XIII 1.1 2880, trans. Andrew C. Johnston)

The tablet is in Gaulish, not Latin, underlining the local pride of the metalworkers.

An archaeologist’s report from 1935 mentions finding many terracotta crucibles with traces of iron, copper and tin. The iron came from the nearby hills, but the tin for bronze-making came from Britain. The Alesians were fortunate here, because while the town wasn’t on a main road, it was near enough to the route from Britain through the Rhone to get the metals they needed. (Allen: 171)

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, mentions their skill in silver-plating:

It was in the Gallic provinces that the method was discovered of coating articles of copper with white lead, so as to be scarcely distinguishable from silver: articles thus plated are known as “incoctilia.” At a later period, the people of the town of Alesia began to use a similar process for plating articles with silver, more particularly ornaments for horses, beasts of burden, and yokes of oxen: the merit, however, of this invention belongs to the Bituriges.

(Natural History XXXIV: 48ff, trans. John Bostock)

Ucuetis’ name is also a local product: he stands outside the Goibniu/Gofannon/Gobannos pattern of Celtic smith-gods. Scholars are uncertain about its meaning, but two theories are considered most plausible. One links it to metalworking, either coming from Proto-Celtic *cuet- “to forge,” giving us “the Good Striker”, or from *okno or “sharp,” making Ucuetis “the Sharpener”. The other says it comes from *ukw- or “to speak or invoke”, so he would be ‘the One who is invoked’.

In light of this, you wonder how the only other record of his worship turns up in another part of Burgundy, at Entrains-sur-Nohains. (Roman Intaranum) Either his cult was more widespread than it seems, or perhaps an Alesian metalworker set up shop there. An inscribed slab on a building, it reads:

In hono[rem domus divinae] / deo Ucu[eti 3] / [di]labsu[m? 3] / [3]RTIR[3] / [3 r]esti[tuit(?) ( AE 1995, 01095)

‘In honour of the Divine House and to the God Ucuetis […] (trans. Noemie Beck)

The dedicator had obviously done well, which might explain the reference to the divine house – the Romans were the dominant power, and it paid to have good relations with them. However, they still chose to honour a Burgundian god under his own name, an act of Gallic pride.

Bergusia

In the beginning, Alesia was a hill-fort on Mt. Auxois. Bergusia’s name comes from a Celtic root berg(o), bergusia, ‘mount’, making her the goddess of the mountain, and by extension the tutelary goddess of Alesia. We only have one inscription mentioning her name, from the neck of the bronze vase found in Ucuetis’ temple:

Deo Ucueti / et Bergusiae / Remus Primi fil(ius) / donavit / v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito) ( CIL 13, 11247)

‘To the god Ucetis and to Bergusia, Remus, son of Primus, offered (that vase) and paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (trans. Noemie Beck)

She was not the only mountain-goddess. Another inscription, from Viens in Vaucluse, names a goddess Bergonia, probably goddess of the Monts de Vaucluse. (CIL 12, 01061) The Aleisan goddess Damona took on the byname Matubergini at Saintes in Charente-Maritime, meaning “high favourable” or else “mount of the bear”. Further afield, the Matronae Berguiahenae in Germany make a Germanic twist on the IE root bherĝh.

Another group of Celtic goddesses have the root brig– ‘high’ in their names, including Brigit, Brigantia and Brigindona as well as the Brigiacea Matres of Spain, variations on the same idea.

Divine Couple

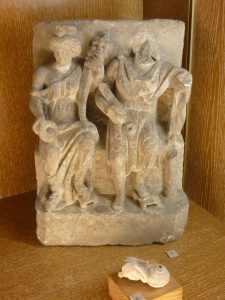

While our god and goddess only appear together in one inscription, archaeologists also found a number of statues of a god and goddess seated side by side. Unfortunately, none of them have any writing on them, and the bearded god with barrel or hammer and his companion look a lot like Sucellos and Nantosuelta.

They often appear on a double throne, suggesting both high status and equality between the two. (Her diadem is also a mark of status.) One or the other holds a cornucopia, or a patera, symbols of plenty and giving, although she usually has the horn of plenty. He sometimes holds a hammer, and in one image has a hammer and a sword. (Sometimes Suellos holds a patera, too.)

Once a wine barrel sits between them, reminding us that this is wine country. Another statue shows a goddess pouring from a patera, while in another the god stows a small barrel under his arm, following the same theme. As Miranda Green points out, the same deity-types occur throughout Burgundy, but there’s no reason to suppose Ucuetis and Bergusia couldn’t be slotted into this pattern.

She was a suitable goddess for a town famed for its metalworking, who were proud enough of their work and their culture to leave a costly stone plaque dedicated to their god under his own name and in his (and their) own language.

PS – Alesia had another divine pair. An inscription found in 1962 pairs local god Apollo Moritasgus with the goddess Damona, whose cult was more widespread. (AE 1965, 00181) Moritasgus’s shrine was a Roman construction built on an earlier Gaulish shrine. After the inscription was found, Le Gall theorized that the broken statue of a woman found at the site must be Damona, and the shrine’s chapel was dedicated to her. So far this remains a theory, for lack of evidence.

PPS – There have been attempts to link Ucuetis with Uchudan/Ugen, named as Ireland’s first smith in the Annals of the Four Masters (Annal M3656.2). The etymology doesn’t really work, however. (Eska: 103, Lajoye: 70)

References and Links:

Allen, George H. 1935: “Excavations on the Site of the Ancient Town of Alesia,” The Classical Weekly 28/22 (Apr. 8, 1935): 169-76. (JSTOR)

Blazek, Václav 2008: “Celtic ‘Smith’ and His Colleagues,” Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics, Vol. 32, Evidence and Counter-Evidence: Essays in honour of Frederik Kortlandt. Volume 1: Balto-Slavic and Indo-European Linguistics (2008): 67-85. (JSTOR)

Eska, Joseph F. “On Syntax and Semantics in Alise-Sainte-Reine (Côte d’Or), Again,” Celtica 24: 101-20. (pdf here)

Espérandieu, Émile and Raymond Lantier 1907: Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, Paris, Impr. nationale, vols. 3 & 9. (Internet Archive: these are huge files. The easiest way to find the images is to search for them by number. III: 2348-57 IX: 7114-9, 7121)

Green, Miranda 2003: Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art, Routledge. (Google Books)

Grigg, Juliana 2002: “The Irish Smith-God Goibniu, and the mythological attributes of the blacksmith,” Australian Celtic Journal 8: 4-15. (academica.edu)

Lajoye, Patrice 2008: “Ucuetis, Cobannos et Volkanos: Les Dieux de la Forge en Gaule,” Mythologie Française 233: 69-79. (academica.edu)

Newell, Adrian N. 1939: “The Dove-Deity of Aleisa and Serapis-Moritasgus,” Révue Archaéologique, 6th Series, v. 14. (July-Dec. 1939): 133-58. (JSTOR)

Sucellus and Smith Gods

arbre celtique (in French)

Bergusia and Bergonia

Map of Celtic deity sites

Alise-sur-Reine has a large statue of Vercingetorix, and another at Clemont-Ferrand commemorates one of his victories.

If you like the image at the top, click here.

Pingback: Smith-gods: Goibniu, Gofannon and Cobannos | We Are Star Stuff

Pingback: Zisa: the Augsburg Goddess or Invented Tradition? | We Are Star Stuff

Pingback: Aeracura: Goddess of the Underworld | We Are Star Stuff

Pingback: Irish Deities/Spirits | The Lefthander's Path