Check out my piece on Cernunnos and Flidais on the Dun Brython blog.

Check out my piece on Cernunnos and Flidais on the Dun Brython blog.

When you consider what Hercules did for Gaul, it’s no wonder that they loved him. He founded the city of Alesia, and introduced the rule of law. “And for the entire period from the days of Heracles this city remained free and was never sacked until our own time…”1 (Diodorus Siculus 4.19.1)

Other myths said that Hercules was the father of Celtos, Galatos and Iberus, the ancestors of the Celts, Galatians and Iberians. This would make him the ancestor of the French, Spanish and Anatolian Celts, who would thus become many-times-grand-children of Jupiter.

To honour their fore-father, they offered statuettes of him at shrines (especially the god Borvo’s), and many Gaulish gods, including Ogmios and Smertrios, were paired with him as part of interpretatio celtica. (MacKillop: 248)

This post exists because of a mistake. When I was researching my post on Sulis, I came across references to a goddess Adsullata, who seemed similar. She was from Central Europe, and I was a bit excited at the thought that maybe Sulis wasn’t alone after all.

Unfortunately, it turned out that Adsullata was Adsalluta. She and her partner, Savus, are unusual in that they are a divine couple who retained their native names, with no Roman overlay. (The Epigraph Databank has eight entries for Adsalluta, seven for Savus, but none for Adsullata.)

Volunteer archaeologists have unearthed a miniature bronze figure of a Roman goddess from Arbeia Roman Fort in South Shields. Helpers from the WallQuest community archaeology project and the Earthwatch Institute dug up the figure of the goddess Ceres which is thought to be a mount from a larger piece of furniture. Ceres was the goddess of agriculture, grain and fertility. Arbeia was a supply base where thousands of tons of grain were stored in granaries to feed the army stationed along Hadrian’s Wall. This is the second goddess that the WallQuest project has found at Arbeia in two years. In 2014, a local volunteer found a carved stone head of a protective goddess, or tutela.

Source: Mini figure of Roman goddess uncovered at Arbeia | Tyne Tees – ITV News

This is an extremely condensed look at the goddess Brigantia. For a much more detailed study, see my book Brigantia: Goddess of the North.

The Brigantian federation stretched over most of northern England, and their queen, Cartimandua, is one of the few female rulers known to history. But the fame of their goddess, Brigantia, comes from a Roman statue.

As curator of the Celts exhibition, I got to spend a lot of time showing people wonderful Iron Age treasures. Some of my favourites were the big metal neck rings called torcs that were worn across much of Europe (and beyond) around 2000 years ago. One of the things I was asked most often is, ‘But how did you put them on?!’ It’s a very good question, seeing as they often look like solid metal rings with nowhere near enough space to squeeze your neck through.

Sometimes studying mythology leads you into areas of human frailty and vulnerability that bring you very close to the past. Any study of healing deities stirs the emotions, partly because we all know the fear that sickness brings, and because so many of the things they suffered from are unknown to us (at least in the prosperous world).*

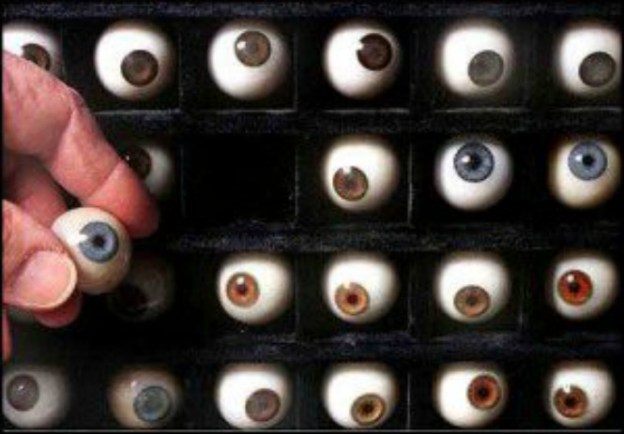

The many offerings of ex-votos, often body parts, found at healing shrines testify to the various illnesses of ancient times. These were not always rich offerings, either. At the shrine of Apollo Vindonnus archaeologists found many votives carved from oak wood or stone. Many were of body parts, but others were of hands holding offerings. (You wonder if they somehow stood for the offering itself, or promised one in return for a cure.)

I thought I was done with deer-goddesses, after the posts on Flidias, hunting goddesses and horned goddesses. Sometimes, however, you’re only done with a subject when it’s done with you. I couldn’t leave this topic without mentioning Carvonia, a Celtic goddess from Central Europe.

Mercury, the travelling god, with his hat and staff and cloak, is easily compared to Odin, the god with the wide-brimmed hat, blue cloak, and staff or spear. Both seem to be able to travel through all the worlds, both are connected to the dead, and both are tricky to deal with. Both rely on their cleverness to get them out of sticky situations.